Dunia’s contribution to a transversal reading of systematized contents of the Forum.

1. Methodology

The present analysis is based on scientific methods of qualitative investigation.

- Stage 1: the reports of each session generated a primary verbatim (2,300 statements for the whole forum), structured according to four analysis categories, namely 1. main points raised; 2. moderator’s summary; 3. objectives and perspectives; 4. main recommendations, supplemented by other metadata (forum day, names of moderators, list of speakers, themes, session category, etc.). This verbatim of a total of 70 sessions was edited and created in an online document repository using the software Fichothèque, in the form of a collection of summary sheets.

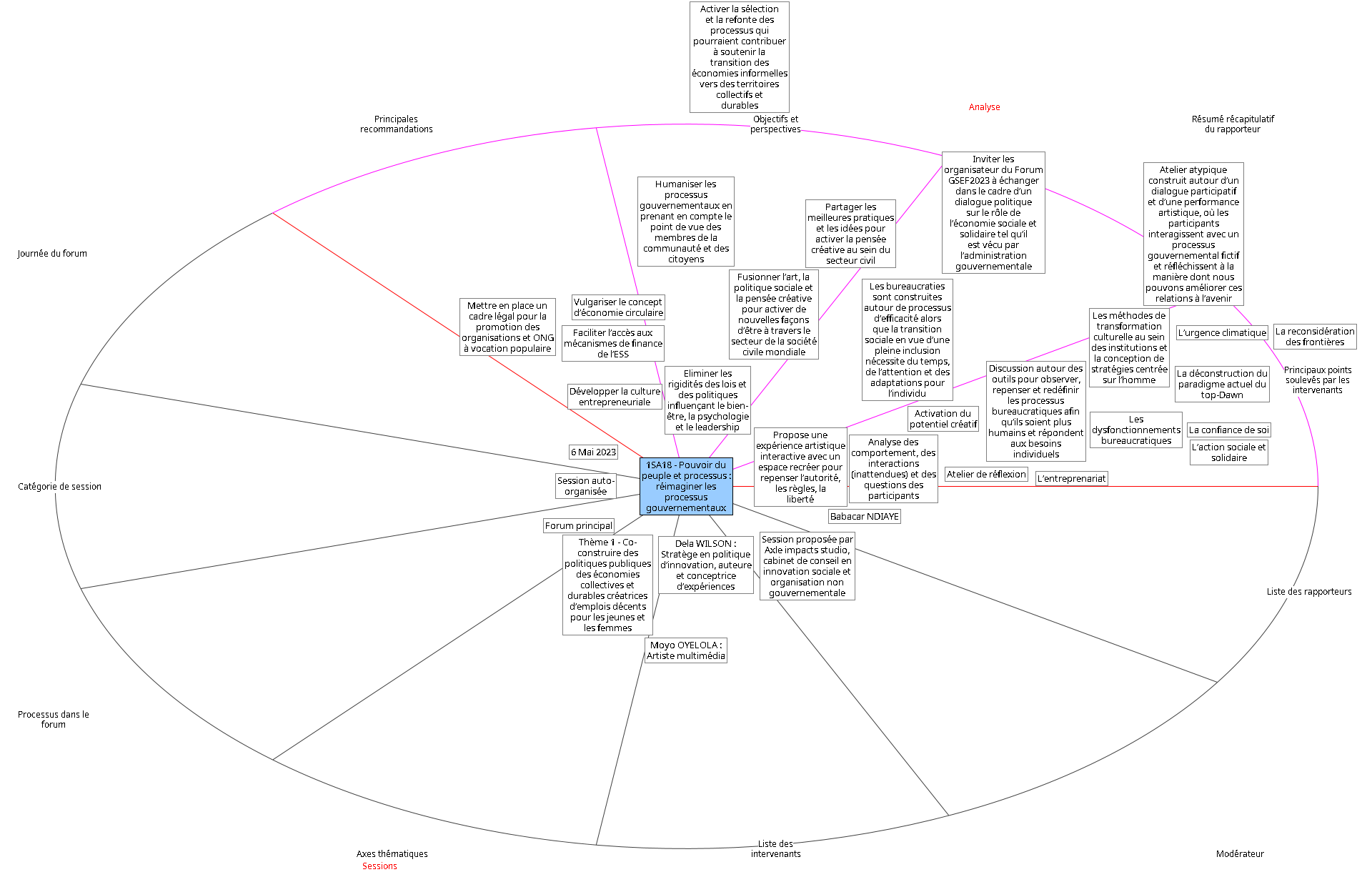

- Step 2: The verbatim of each session was conceptually mapped (or mind-mapped) using Desmodo software (https://desmographies2.desmodo.net/gsef). The result is 70 initial concept maps, distributed according to the forum’s seven themes, representing a synthesis unit for each forum session.

Concept map of session 1SA18. The session’s primary verbatim and metadata are positioned as rectangular descriptors in their respective analysis categories (indicated on the periphery of the map).

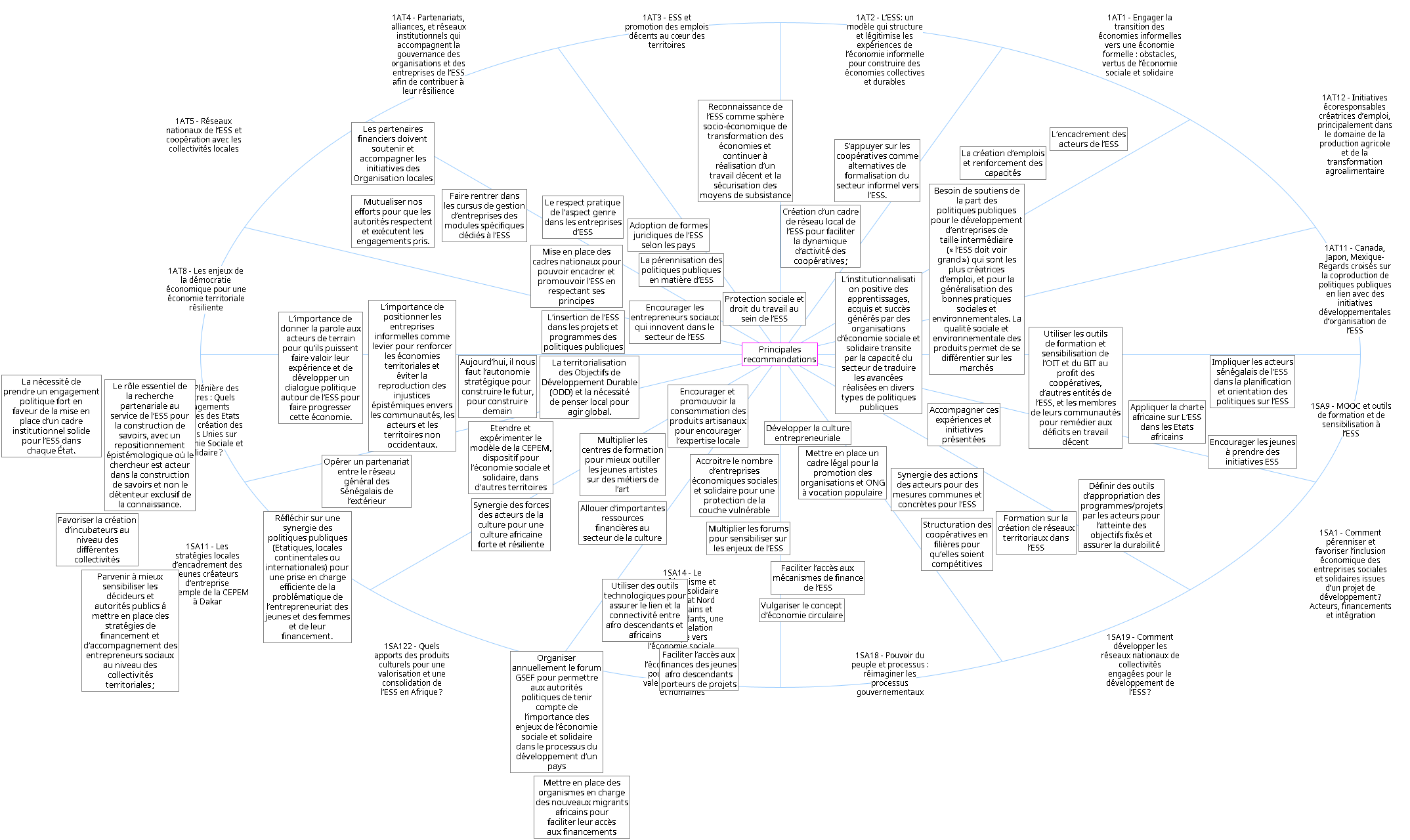

- Step 3: A first stage of interpretation is carried out on the basis of inverted concept maps, i.e. a visualization that places one of the four analysis categories at the center and brings together the descriptors of all sessions of a given theme or of all themes. Reading this verbatim, visualized from the angle of each initial analysis category, enables us to sketch out a new system of meta-categories, this time based on the content of the verbatim. These meta-categories are produced intellectually, through iterative reading of the inverted maps, with the aim of identifying common elements of strategy and perspectives for change (or divergence, rupture, etc.). In this way, we arrive at 23 strategic axes with significant consistency across all themes (meta-categories that are too marginal or anecdotal are not retained). During this stage, a second synthesis unit is drawn up for all themes, i.e. for all systematized sessions.

Inverted map of the Main recommendations category. The verbatim of sessions in theme 1 is gathered around this same category (center) and linked to the reference session (map periphery).

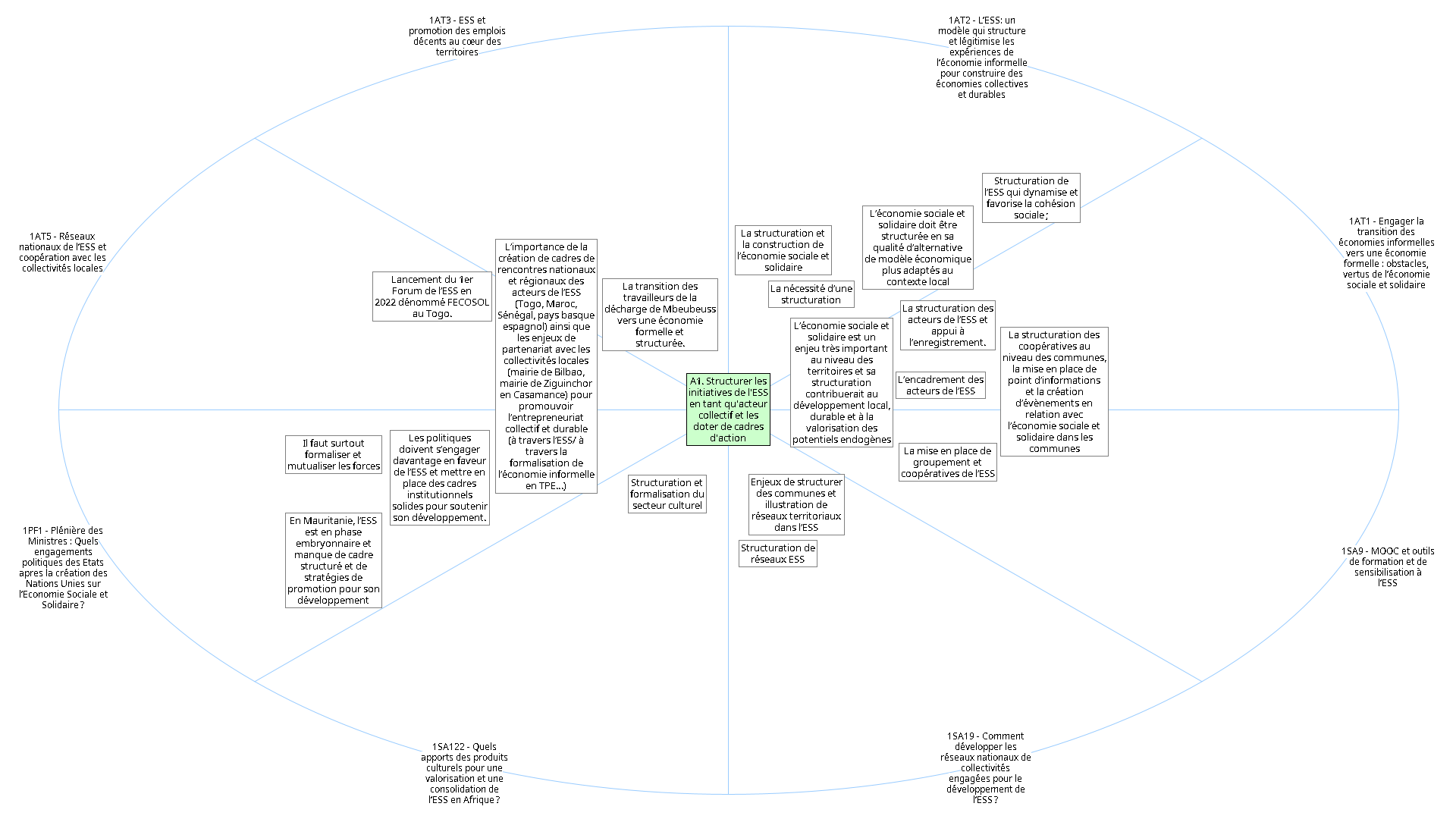

- Step 4: the verbatim on which each new meta-category of analysis is based is mapped within a new generation of concept maps. The result is 23 new concept maps for all strategic perspectives.

Conceptual map of strategic perspectives A1 (center). The verbatim underlying this perspective (rectangular descriptors) is positioned according to the initial sessions (periphery) during which it was uttered.

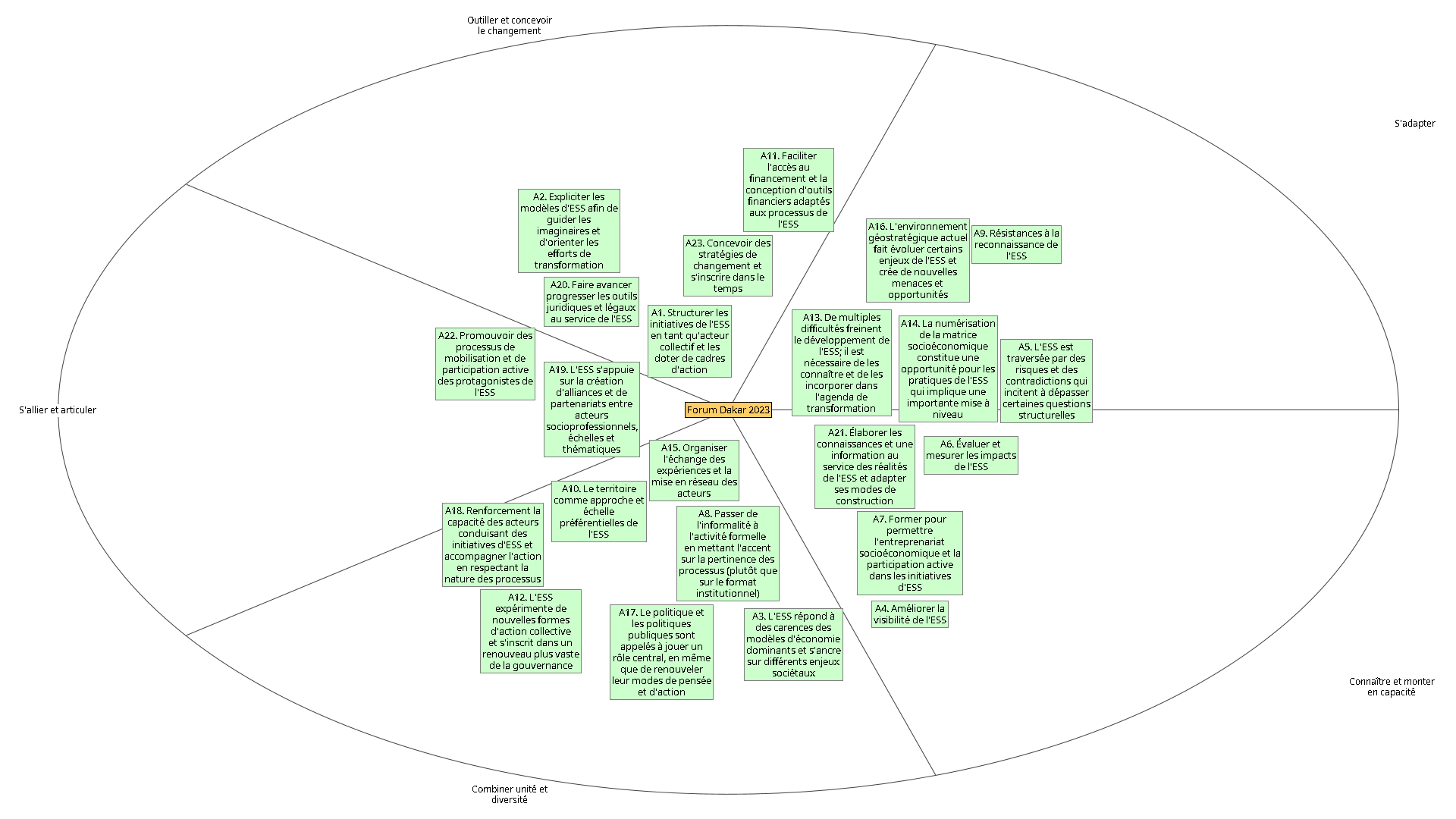

- Step 5: In the same way, the 23 themes are analyzed to identify new meta-categories. Five perspectives stand out and give rise to this synthesis map.

Cartography of the 23 strategic perspectives (rectangular descriptors) of the forum (center), positioned according to the 5 major emerging perspectives (periphery).

Such an exercise in inductive and abductive reflection cannot be separated from the intellectual and therefore subjective prism of the author who has produced this interpretation (François Soulard), bearing in mind that it can of course be produced more collectively or enriched by other contributions.

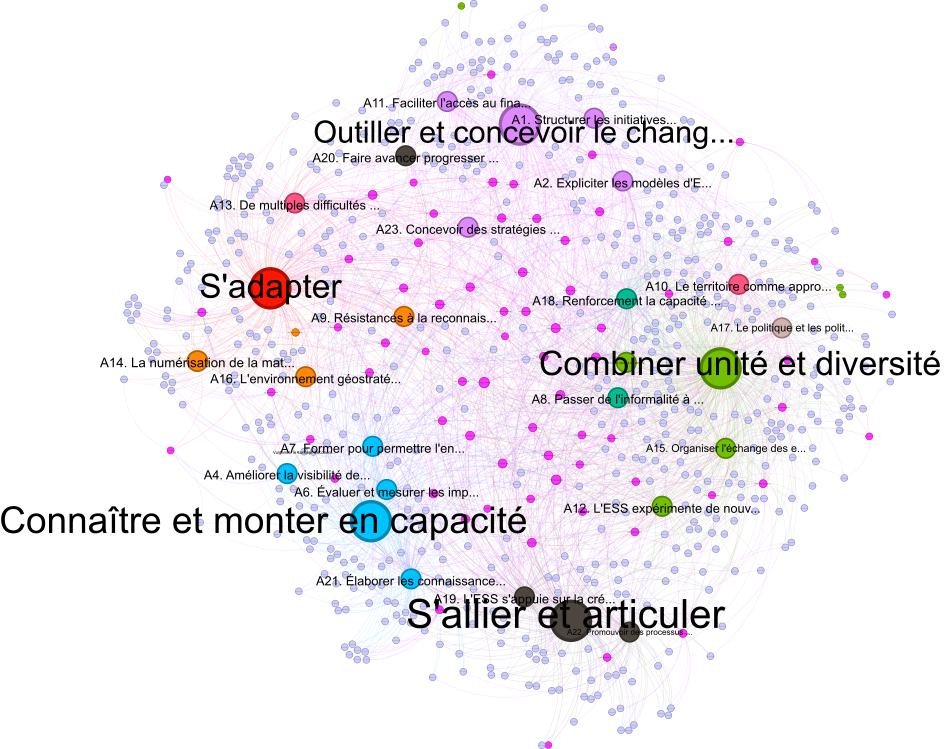

Finally, once structured in the form of a relationship table (axis 1 -> verbatim1 axis 1 ->verbatim3 ax2 -> verbatim5…), the primary verbatim, the 23 strategic perspectives and the five emerging ones can be visualized in the form of a network graph (or several) using the software Gephi.

Network graph calculated from primary verbatim, sessions, 23 strategic axes and 5 emerging axes.

Open in SVG format : https://dakar2023.gsef-net.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/07/Untitled.svg.

2. Five main themes emerge

Five major perspectives emerge from a transversal reading of the 70 systematized sessions. Such an overall vision, irreducible to the diversity of the contributions expressed in Dakar, represents less an implicit consensus of the participants than a heuristic search for common perspectives likely to give meaning to the overall movement.

Adapting.

The world has changed rapidly. COVID-19 has precipitated the perception of a new geostrategic environment based on sharp competition between old and emerging industrial states with a strong desire for autonomy, including in Africa. On a multipolar chessboard more divided, fragmented and criss-crossed by globalized conflicts (Ukraine) or politico-religious conflicts (Africa), climatic, economic or health interdependencies are superimposed (COVID-19), exacerbating earlier tensions, always depending on the context. The contemporary economy, transformed by digitalization, also accentuates inequalities and the disarticulation of territories. If the ethic of solidarity continues to resonate particularly strongly in this harsher world, the understanding framework built around the notion of sustainability, abundantly set out in the sessions alongside other UN categories (blue economy, green economy, etc.), is no longer sufficient to orient oneself in this new environment.

In this sense, the SSE is invited to position itself in front of the “world of tomorrow”, which has become tangible. The forum sessions emphasize that the social and solidarity economy is at the service both of these evolutions seen in a positive light (greater autonomy for nations and communities) and of helping to counterbalance their negative aspects (climate change, social resilience, regional integration, inclusion, rebalancing of territories). The potential of the social and solidarity economy, as well as its legitimacy, lies in facing up to these challenges. The UN’s recognition of the social and solidarity economy in 2022 echoes this concern and opens up a window of opportunity.

With this in mind, one of the key words is “adapt”. Firstly, to this changing world, which in many ways extends into the lives of local communities, and secondly, to the new rules brought about by the contemporary economy. Whether we like it or not, digitization has reshuffled many cards, revealing new vectors of wealth creation, risks and opportunities to be seized. Many of the definitions and reflexes stemming from the dominant capitalist paradigm – whether in terms of approaches to informality, financing, digital technologies or modes of economic exchange – persist in the diffuse world of the social and solidarity economy. The debates show that all its dimensions – thinking, organization, modes of action, institutional frameworks – are affected by organizational, cognitive, cultural and financial inertia.

This demand for adaptation thus brings to the fore one of social economy’s raisons d’être. As an economy closely linked to a political aim, it invents itself according to the needs and cohesive objectives it intends to pursue. The obstacles created by the contemporary economic matrix are therefore an integral part of its roadmap, and become questions to be addressed critically and lucidly.

Combining unity and diversity.

The Dakar debates very often refer to the idea of collective experimentation, i.e. the development of atypical or innovative modes of organization. The debates take this idea a step further, by evoking the insertion of collective action into a broader mutation. The art of reconciling unity and diversity lies at the heart of this equation. Anchoring ourselves in endogenous knowledge, rooting ourselves in the needs expressed at local level, relying on the protagonists of initiatives go hand in hand with the search for common visions and frameworks, and shared co-elaboration. Crucially, the search for unity goes hand in hand with “growth in diversity”. It’s less a question of “copying and pasting” existing recipes, or of applying off-the-shelf approaches superimposed on existing realities, than of developing bottom-up responses by bringing together a mosaic of players and experiences.

As some of the workshops emphasized, this modus operandi represents a real turnaround. How can we increase the plurality of social and solidarity economy forms while reinforcing adherence to common objectives? This search for a positive-sum game between unity and diversity fuels a creative link between the local and the global. Hence the importance of flexible, learning processes, rather than the reproduction of pre-established institutional forms. The mechanisms of dialogue, co-construction of initiatives, and territorial intelligibility are thus promoted as priority modes of action. The territory – or community – is seen as the scale par excellence of the social and solidarity economy, envisaged both as a level of action and an approach to be favored in initiatives. Some workshops go even further, envisaging territories as a new collective player alongside the market, the state and civil society.

As a consequence of this dialectic, we need to think creatively about how to translate action frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or other national SSE frameworks onto the ground. Here too, it is contradictory to transpose such frameworks, and the tools they convey, “vertically” to territorial realities. From this point of view, the essence of sociald and solidarity economy appears as a flexible modality for developing projects in response to local needs, in a logic of subsidiarity with higher levels of governance.

Another consequence of this philosophy of action is capacity-building and support, as well as the exchange of experience and networking. These four lines of action are asserted loud and clear in the modus operandi of the “organized collective being” at the heart of the social economy. The complex nature of the social and solidarity economy calls for an ecosystem of support and capacity-building, particularly in terms of knowledge, as we shall see below. Exchanging experience and networking are the means to build relevant learning from experimentation itself, and to articulate scales of action.

The insistence on this unity-diversity relationship, which was not very explicit in the sessions, nevertheless suggests that the social and solidarity is evolving in a theoretical and praxeological hollow on this issue. The weight given to this axis in the Dakar debates argues in favor of greater intellectual investment in the matter.

Allying and articulating.

Some workshops compared the social and solidarity economy to a “handshake” economy. The building of alliances and partnerships was indeed a constant theme in the debates, and took on different dimensions. On the one hand, they enable social economy approaches to expand. It’s a question of seeking out professional and international cooperation in order to strengthen transformative processes and aim for a change of scale, or at least an articulation of scales of action. On the other hand, building partnerships is the very substance of social and solidarity economy processes. Here and there, experiences emphasize the fact that they are built on relationships. Bringing together players who are locally separated due to the absence of public policies or the tropism of development models, and articulating themes that remain compartmentalized due to the organ-pipe functioning of the socio-political matrix, are two essential components of the debates.

Placed in the territorial perspective highlighted above, the social and solidarity economy takes on a deeper meaning: that of providing tools for rebuilding the horizontal coherence of territories subjected to new dynamics of disarticulation – and conversely relocalization – in the current phase of globalization. As a result, the social economy is converging with other approaches that share this objective of restoring coherence: food sovereignty, local trade and short circuits, participatory finance, local democracy and citizenship, open-source software and appropriate technologies, inter-municipality, migration, integration and entrepreneurial culture, local responsibility of industry and business, and so on. The workshops reaffirmed, more or less explicitly, that these fields of activity are likely to work towards the same policy of horizontal cohesion of territories, which implies adopting a vision, frameworks and mobilization processes to generate these synergies that are always complex to establish. The sessions’ insistence on a partnership that goes well beyond the thematic delimitation of the social and solidarity economy shows that this aspiration to bring players together refers to a genuine policy of creating synergies between territories. This is seen as a means of giving greater political consistency to the social economy.

As a corollary to this line of thinking, we need to encourage mobilization processes and promote active participation, as suggested by a number of thematic areas. Many forms of participation are suggested in the sessions, always depending on the contexts in which they are rooted. Here too, the quest for participation by the various protagonists is based less on an obligation of means (compliance) than on an obligation of result (creativity of processes). What’s important is not the form of participation adopted, but rather the relevance of the process in guaranteeing social roots, active protagonism and autonomous support for initiatives.

Such processes, which are particularly demanding in terms of collective intelligence and energy, involve reversals of practice and perception within strategic cultures.

Knowing and empowering.

Know to adapt, act in a context of great diversity, join forces with others and transform. This seemingly trivial continuum emerges clearly from the forum. The knowledge imperative is expressed from three angles. Firstly, the ways in which knowledge is developed in the social and solidarity are called upon to be in phase with the nature of the processes involved. Once again, we see the search for relevance, i.e. consistency between ends and means. In other words, a constructivist, systemic, interdisciplinary and pragmatic approach is essential to any territorial approach, partnership-based and participatory dynamics, or any detailed understanding of social economy processes. This calls for an epistemological renewal.

In fact, these modalities first require the deconstruction of dominant modes of knowledge. The sessions at the Femm’ESS forum clearly show how social and solidarity projects have to confront all kinds of stereotypes and preconceptions that contribute to maintaining the segregation of players. These more appropriate modalities (research-action, collaboration, researcher-actor alliances) must also be applied to scientific research, which was very much in demand in the sessions to support the solidarity economy’s rise to intelligence.

Secondly, the qualitative renewal of cognitive processes must be matched by a quantitative training effort. From schools and universities, from civil spaces to the inner workings of social economy projects, the aim is to generate training dynamics capable of putting players in a position to understand and undertake, by mobilizing technical and organizational dimensions, which is not necessarily synonymous with traditional academic knowledge. Training refers to the more mobilizing sense of increasing individual and collective capacities to act in a context that demands demanding transformations. Sharing experience, as we saw above, is one of the cognitive approaches to be encouraged.

Finally, as an extension of these last points, the sessions revealed a lack of knowledge about the scope of the transformations conveyed by the social and solidarity economy. It is necessary to develop impact measurement and evaluation in social economy projects, which also leads to innovation in study methodologies. The evaluation of projects is thus called upon to respond less to an exercise in objective qualification than as a lever of collective intelligence promoting learning.

Finally, the sharing of information is mentioned as a factor conditioning coordination between players.

Tooling and designing change.

The four strategic perspectives above imply a series of particularly complex changes to implement, which inevitably raises the question of the collective body capable of driving such a transformative agenda. Should the SSE movement consolidate itself by relying on the spontaneous spread and accumulation of a multitude of local initiatives? Or does it need a strategic roadmap to guide the imagination, seize opportunities and focus action on certain levers? While the magnitude of the forum made it difficult to explore this question in detail, participants did seem to favour the second hypothesis. In a word, the SSE, in addition to learning more about itself, now needs to better design changes within the systems in which it operates.

To this end, we have identified five key areas of focus: long-term commitment; articulating different scales; structuring initiatives; building models; and equipping approaches (culturally, legally and financially). In both cases, the aim is to build relationships between different scales. In the first case, it’s a question of time (the present, or even the urgency in which projects are woven, the medium term and the long term). Scale of governance for the second (locality, province, state, region, world). The emphasis placed on the long term indicates a weakness at this level, while the national and international scales seem to be the priorities in terms of political echelon.

The structuring of initiatives, strongly emphasized, is a preferential vector for consolidating initiatives and encouraging changes of scale. In a social and solidarity economy context still perceived as embryonic, participants called for the creation of consultation frameworks, national and international processes, the formalization of partnerships and the institutionalization of initiatives (cooperatives, groups, associations, companies, etc.). Moving from informality to an institutional framework is important to scale for initiatives. But attention is focused above all on the processes that make up this structuring, with the mobilizing power of the agenda, working methods and joint projects run as a network being deemed more significant than any institutional configuration.

Hence the role played by social and solidarity economy models, which embodies its promotion and projection within society and its challenges. How does social economy offer an alternative and address macro-economic issues? What wealth does it bring and how important is its social dimension? As mentioned above, the social economy model that emerged from the sessions is that of an economy committed to rebuilding relationships and coherence in territories, rooted in local socio-economic needs and operating according to organizational arrangements that simultaneously achieve the objectives of wealth creation, inclusion, citizenship, participation and articulation of sectors of activity.

Finally, cultural, financial and legal tools are two sides of the same coin. Financial support aims to sustain ecosystems that enable social and solidarity initiatives to emerge and become sustainable, in ways that are adapted to their realities and not calibrated to traditional market criteria. The creation or reinforcement of legal frameworks for the social economy is a prerequisite for the recognition and structuring of players. Finally, the cultural dimension refers to the methods that need to be deployed to undertake the cultural transformations that go hand in hand with social and solidarity economy.