A contribution to the Social Internet Forum debates

In the space of twenty-five years, cyberspace has raised the upper echelons of global power to become a geostrategic asset like other traditional spaces such as international waters, the atmosphere, and space. The speed with which it has ascended is unprecedented in history. Never before in times of “global peace” (or rather, in the absence of a global war) have we seen such a rapid development of a new dimension of planetary interdependence, in which political, military, economic and technological aspects are simultaneously in play, as well as many social and institutional players, with greater density in the advanced economies. After a first stage in which the internet evolved relatively in the shadow of competition among major powers, we are now in a new stage in which the traditional players on the geopolitical chessboard, particularly industrial states and transnational corporations, are really making their mark. Files released by Wikileaks in February 2017 show once again this worrying degree of colonization of the World Wide Web and the interests in play.

Indeed, not a year goes by without some new aspect of the dispute over the internet or a new scandal over Orwellian control of new digital resources. In 2013, Edward Snowden marked a watershed in digital history that no educational action could have done, when he revealed the many-tentacled magnitude of the interception apparatus implemented by the USA in alliance with other industrial countries and major digital corporations. In 2014, it came to light that the NSA had been spying on Presidents Dilma Roussef and Angela Merkel, hastening the organization of the multilateral NetMundial meeting in Brazil in 2014 and institutional reforms in the way the internet infrastructure is regulated (de-Americanization of the ICANN). In the USA in 2016, the National Democratic Convention email leak directly influenced the presidential elections.

The growth of this climate of surveillance has its correlation in the way the digital industry has become progressively hyper-concentrated. Today, five US companies (Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Amazon and IBM) have absorbed a large chunk of world data. The duopoly of Google and Facebook in 2016 captured 95% of the total of internet advertising revenue, while the Alphabet conglomerate, owner of such household names as Google, Gmail, Youtube and Android, became the largest global communications company, encouraging convergence among various branches of technology (bio-nano-IT-cyber.) These facts, outstanding on the surface, are in reality epiphenomena of an increasingly extensive and thicker continent (an “eighth continent”, as Nigerian IT expert Philip Emeagwali dubbed it in the 1990s), in which a growing conflict and a higher degree of dispute can be seen.

If we enter cyberspace through the door of the heavyweight players and the surveillance/corporate concentration axis, it is because it allows us to highlight a central element that characterizes the new rules of play in place in the electronic terrain. The arrival of these major players in the electronic terrain has brought about a paradigm shift in the forms of intervention on the web and to some extent truncated the first ideological systems that had designed the earlier stages of increased internet use. Arising from a horizontal, decentralized space, and originally invented by US and European engineers with military funding as part of the ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency), the internet was fed by a libertarian conception of autonomous exchanges and was developed until 1984 as an inter-university structure in a climate of openness highly favourable to technological innovation that then expanded exponentially with the liberation of network protocols from 1993.

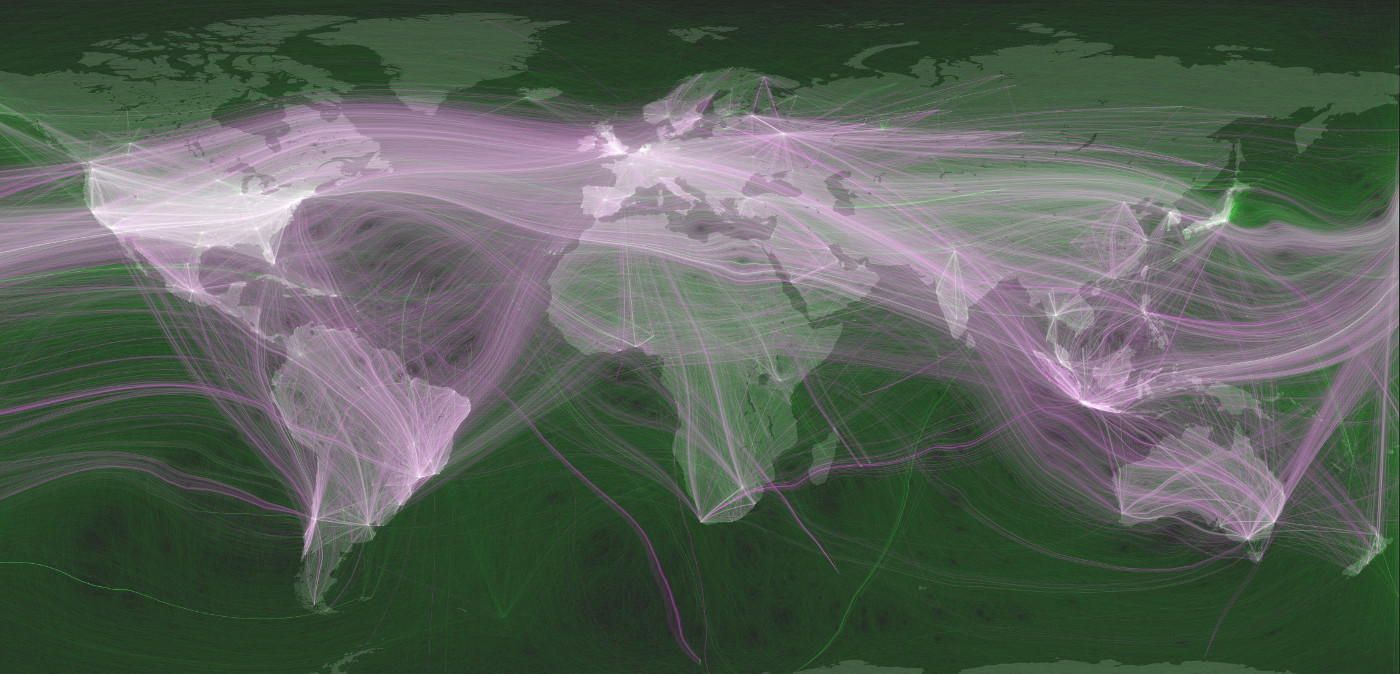

The industrial players that entered from then on were supported by a framework that very effectively combined normative unity (domains, protocols, routing) and physical decentralization (fibre optic lines, exchange points, agreements between networks, hybrid financial investment in material infrastructure) in full progression and economic competition of (re)emerging powers. The electronic space gradually positioned itself at the heart of the interests of these powers, within a geo-economic order hegemonized by the United States with low-level regulation, which ended up turning the web into a spinal column of the global political and economic agenda, while at the same time transforming the power matrix and socio-productive models.

This leap from micro-electronics to global power not only generates a mere technological evolution. Rather, it is a question of a profound movement that triggers a number of ruptures in socio-technical balances, clashing also with limited political regimes that do not have the political, cultural, constitutional or legal resources at their disposal to deal with the nature and speed of the phenomena. The logical mechanisms of the internet, code and algorithms, are the law, as announced in a pioneering manner by Lawrence Lessig in 2000. One need only see how other types of technological innovations such as transgenic seeds or chemical inputs have permeated very rapidly under pressure from productivist growth in all the interstices of the Westphalian liberal system. The Chinese “cybernetic wall” is an eloquent counterexample of a centralized barrier to dealing with sovereignty in the insertion in the global digital flow without being left out of the digital race. Zygmunt Bauman summed it up well when he said that globalization has led to a world where “there is local politics without power and global power without politics.”

Some of this is true in the field of cybernetics and IT, in close ties with the neoliberal geo-economic project that the global elites bring to the expansion of the internet and a possible fourth productive revolution sustained by their “biopolitical” factories of consensus. In fact, the not just institutional but also cultural framework of interpretation on which the multilateral approach of cyberspace rests is still highly instrumental and unfinished (1), far from elevating a political dimension based on the idea of strategic commons or of a new vector of the distribution of wealth. This sub-politicization on the formal plane has not hastened an effective world governance of cyberspace, but rather a consensus of techno-economic administration consolidating a group of sectoral players and interests (2).

Given the emergence of these disturbing elements, many questions, readings and struggles have been disseminated, with a great variety of ideological currents running them (neoliberal, idealist, techno-centrist, libertarian, sovereignist, obscurantist, etc.) In fact, there is no single collective subject capable today of ordering a strategic agenda to fight on a local or global level. So be it; the challenge clearly lies in forming new alliances and perhaps an ideology to go deeper into the political dispute. However, the historical perspective shows that the challenge is not to be found so much in the subjects or the social struggles that always rise up against forms of exploitation, but in the forms of domination and inequalities that are reconfigured in new structures and with new characteristics. This is seen to be true particularly in the electronic territory. Consequently, we turn to a great imperative of renewing the internet’s frameworks of understanding, that not only have to do with so-called new information technologies, but also with the modalities of evolution of world power, the socioproductive matrix and all its interfaces with the cybernetic and communicational sectors. In practice, this renovation comes up against resistance because of the boundaries between technical, political and conceptual cultures.

We may also add that it is necessary to do this work with a view to forming a new geometry of power at global and continental level, in a new stage where the transition towards an unstable multipolar system leads to a reappearance of neo-nationalism and aggravates the competition between states to within each strategic commons, cyberspace being especially prone to a generalized conflict in the Hobbesian style; in other words, the ripening of conditions for trampling on securities, rights and civic liberties at the altar of commerce and rivalry between powers. It is vital that new consensuses and rules be written up before power relations generate changes or ruptures that will be hard to reverse (as was historically the case with deep sea resources and maritime navigation, transitioning from a realpolitik regime to a set of rules and penalties codified in international law.) Furthermore, if we admit that the fragmented chessboard of democratic-liberal entities is increasingly left out in the cold by an ever-hardening anarcho-capitalism and that the crucial issues on the agenda are to be found at transnational level, the emergence of a plural and plebeian power space like cyberspace triggers a debate on the conditions of a “transnational democratic pre-system” (or an online global democracy, so to speak). Ultimately, the internet, as a vector of the process of globalization, is a social construct that carries a given pattern of globalness that has to be signified according to its historic moment. This reasoning allows us to connect the techno-economic dimension currently dominant on the internet with the political and ethical dimension.

All this leads us to converge on two axes that we want to recontextualize briefly in light of the Latin American trajectory. Firstly, the dispute over the internet and the sovereign appropriation of cyberspace cannot be separated from the construction of strategic, political and intellectual viewpoints and skills at the service of a transition in the regional economies and therefore of the wealth matrix. There have been unprecedented state initiatives in Latin America to develop a digital citizenship and a technological sovereignty within a movement to recover political sovereignty (3), but these have been left inconclusive due to the lack of political will or overshadowed by the supremacy of a financial model that seeks a return to a prime materials economy, something very common in the elites, including those of the popular-progressive field. The economist Ladislau Dowbor stresses that the financial stranglehold and mass extraction of wealth (whether informal or formal) was a central factor in the social and political collapse in Brazil after the destabilization resulting from the 2008 financial crisis.

The situation is similar in Argentina and Venezuela and in some African countries with a dependent structure. In Europe, in contrast, it is the absence of a joint political project and therefore of a strategic vision that has left major parts of the knowledge economy and cyberspace in the hands of alien interests. As noted in the draft of the Consensus Of Our America, there is a great need to update the continental political forces to face up to new social and economic structures, that is, reinterpreting an economic matrix that has made the systematic extraction of wealth more sophisticated and which also runs from the centrality of the means of production towards one that incorporates major immaterial factors in a context of global deflation, with new risks of colonization and also with opportunities for emancipation. All this opens up a fertile political terrain to dispute in many areas and beyond historical currents (developmentalist, socialist, structuralist, etc.) an insertion of the new technologies within the aims of economic sovereignty (4), of social justice and inclusion (inclusion that is at once monetary, financial, cultural, technological and political.)

Secondly, efforts by various civil or institutional sectors to defend an internet that is open, plural, neutral, free and transparent should focus on being resignified and radicalized given the degree of technological convergence and colonization attained by corporate power. Various legal battles have been won to strengthen web neutrality and consolidate the right to communicate, even at constitutional level in various South American countries. The use of open code and open standards has multiplied and been internalized in an uneven and unequal manner, but extensively, from the highest institutional level down to various social sectors. New coalitions and spaces of debate have been formed (World free media forum, Internet social forum…). However, as mentioned above, the speed of evolution of the communicational empires puts us against the ropes and forces new scenarios to be assimilated with great intellectual mobility.

If the promotion of free software and open knowledge was a first transforming imaginary in the heyday of microcomputing, today it is also a question of generating consciousness about the hypermonopolization of web services, or making algorithms transparent and generating traceability of the automations that influence many human activities. Although until quite recently the democratization of access to digital services was a pending issue, today it is a question of facing up to an industry of corporate-state commercialization of data (and formats) that takes users’ rights and privacy, exploiting gaps in laws and regulations. If previously it was a question of rebalancing the powers and paths of access to communication networks in national frameworks, today it is necessary to decolonize a communication that quickly unifies the internet, multiple communication supports and concentrated providers of content in the shadow of international standards. That is, there is a qualitative leap in the nature of the struggles in direct relation to the change in the rules of play in cyberspace that we outlined above. Faced with this rapid evolution, it will be necessary to redefine the types of resources and goods that emerge from planetary connectivity and design new regulation models.

Although the battle is highly asymmetric in proportion to the weight of the players, this is no reason to adopt a mimetic or solely defensive stance. Ultimately, there is no guarantee that the politics that turns its back on the real challenges of society will be long-lasting or pertinent. It is true that we are in a stage of recolonization of the electronic networks where the commercial, reductionist logic advances much faster. However, as the American-Argentine mathematician Gregory Chaitin demonstrated, what is at the heart of current social transformations is beyond precisely any “algorithmicity” and automation resources. Ultimately, the levels of resistance do not necessarily coincide with the terms that the monopolies are proposing. This is a battle with a broader paradigm: algorithms of real power versus values and collective intelligence; corporate capture of digital resources versus responsible, shared collectivization of tangible and intangible goods; instrumental modernity versus civilizing transition. It is a great motive for tying together disparate resistances and consolidating one’s own emancipating vision of the electronic networks at the service of popular interests.

Notes:

(1) The World Summits on the Information Society (WSIS) have put together the following definition of internet governance: “The development and application by governments, the private sector and civil society, in their respective roles, of shared principles, norms, rules, decision-making procedures and programmes that shape the evolution and use of the internet.”

(2) Internet et les errances du Multistakeholderisme, (“Internet and the Wanderings of Multistakeholderism”) Françoise Massit-Folléa, IFRI https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-etrangere-2014-4-page-29.htm

(3) UNASUR fibre-optic ring, info-educational programmes—Conectar en igualdad, Canaima, Ceibal—cybersecurity group in the MERCOSUR and UNASUR, Sumak Yachay/FLOR society in Ecuador, national laws in favour of the right to communication, of open standards and free software, etc.

(4) See also the document Latin America First http://www.latindadd.org/2017/03/15/latin-america-first/