Two years have passed since the 2019 electoral crisis in Bolivia. On October 20, 2019, the Andean country plunged into a chaotic situation that brought Evo Morales’s presidency to an end, which had begun in 2005. Contrary to many opinions consolidated throughout the continent and abroad, that crisis did not originate in a coup d’état engineered by the political opposition to the MAS (Movement for Socialism), the networks of the US embassy and the OAS (although they have constantly exerted influence on multiple levels).

Its main cause was a citizen uprising triggered by the irregularities of the October 2019 elections, amplified by the authorities’ refusal to make the elections more transparent and thus respond to the Bolivians’ wishes. The power vacuum created by this crisis was used by individuals who were very far from wanting to achieve the “national reconciliation” intended by the transitional government led by Jeanine Añez Chavez as of November 10, 2019.

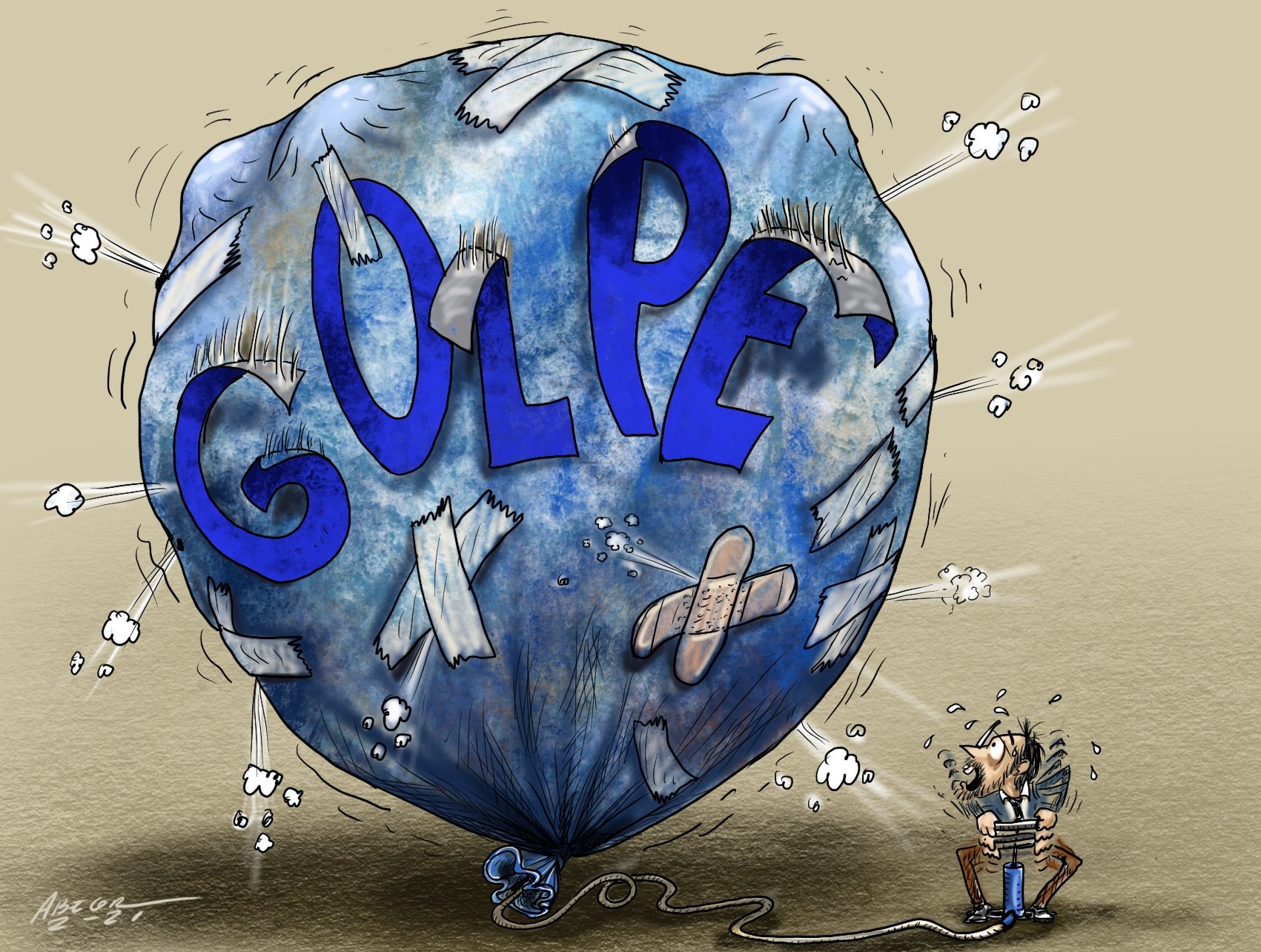

What is the explanation then for the swift acceptance of the coup d’état argument by various sociopolitical sectors and that the electoral fraud was overlooked? How was it possible to stage a coup d’état? By means of an information war, launched to shift the interpretation of the conflict to a more offensive and legitimate place. This concept explains primarily how the MAS carried out its counter-offensive and succeeded, with intelligence and cunning (but also with limits and imperfections), in building an understanding of the facts around the coup d’état narrative.

Cornered by the citizen mobilizations that pushed it against the wall on October 20, 2019, the MAS reversed the modalities of perception of a situation that threatened to seriously undermine its legitimacy. It had to keep this objective covert and stay below overly intense thresholds of provocation by violence. The adoption of an offensive stance, cunning, polemics, exploiting the opponent’s weaknesses, the incitement to fault, denigration, the alternative production of knowledge and the siege of perceptions were inseparably linked to the other strategic maneuvers that took place in the material, institutional and political spheres. Eventually, the interaction of all these components made it possible to change the power relations and reduce the cost of the crisis started by the ruling party. The detailed stages of this process are described in this public study published at the end of August 2021.

A year later, in October 2020, the MAS won the elections under the proper conditions, thanks to its better structuring and a divided opposition. But the result after two years of medium-intensity conflict was a crisis in the Bolivian political system set off by the initial election irregularities but whose roots should be looked for upstream. Faced with the challenge of ensuring continuity within the promising constitutional framework that it had established in 2007, the main Bolivian political force has clung to an authoritarian reflex, in violation of its original premise and with the immediate cost of a gap in terms of human rights, impunity, social polarization and the use of violence.

This type of information confrontation is not exclusive to Bolivia. Since the 1990s, Latin America has been and continues to be a laboratory for economic and information warfare. However, not as much attention has been paid to the new grammar of information confrontations. The conflict at the end of 2019 in Bolivia is an example of the new modalities to which a dominated—or temporarily dominated—actor can resort to counteract a story, rebuild legitimacy, exploit the weaknesses of his opponents and ultimately reverse a balance of power through knowledge and opinions.

More broadly, the communication monopolies, so characteristic of the South American continent, now face an asymmetric communication fabric capable of defeating them in battles. Among others, the emblematic case of this phenomenon is Venezuela, where a very intense information war of no more than twenty years has given an advantage to the opponents of a change of regime in Caracas.

These information confrontations between weak and strong actors cannot but reveal some weaknesses of the North American hegemonic system in the subregion of which the OAS is a part. The normative, cultural and economic weight of the United States remains comparatively considerable, regardless of the more or less orthodox relations with the southern hemisphere. But it is clear that several blind spots in its strategic culture (for example, its excessive force projection, its uniformizing cultural character or its support for inconsistent political groups as in the 1950s and 1960s) and its normative format have opened the door to new oppositions in another guise. Central America is no longer Washington’s “backyard”. Nicaragua, Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia and even Ecuador are openly showing their dissent and have not given in despite economic sanctions and being subject to many pressures from the OAS. As elsewhere, more or less hard or soft plans for regime change have not produced the desired effects.

Everything indicates that these information battles will continue to be particularly intense. For Latin American nations, which constantly struggle against their disparities and dependencies, the danger is that this evolution in power relations may encourage the building of prosperity less than the temptation for “dissident entrepreneurs” to capture popular aspirations and lead them to far less promising places.